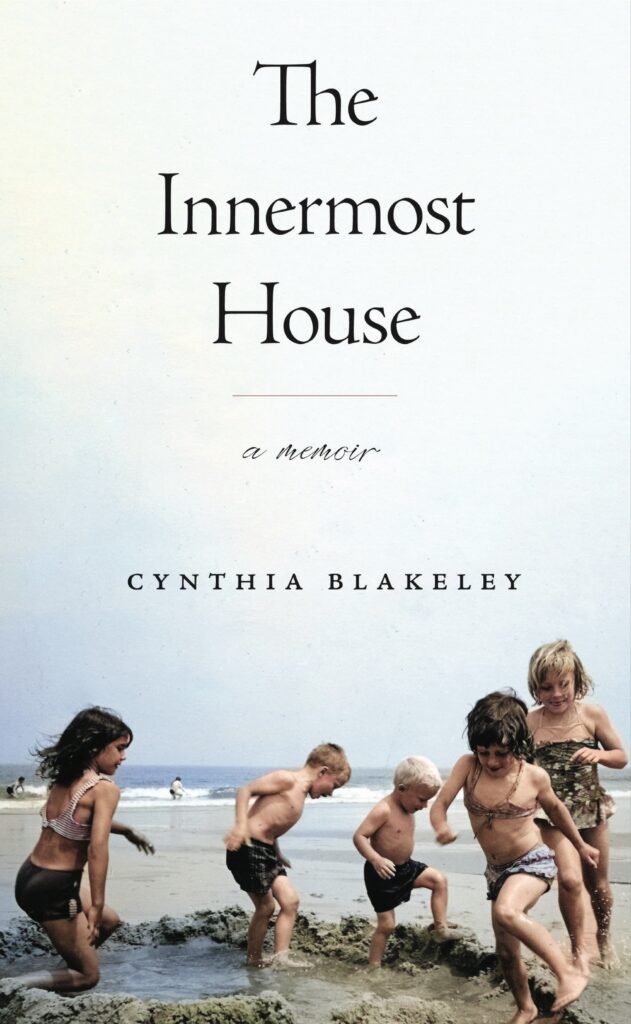

The Innermost House: A Memoir

Listen to an interview: New Books Network (July 2025); WCAI (Jan. 2025); WOMR (Dec. 2024)

Read a review: “The Inner World of an Outer Cape Childhood,” The Provincetown Independent (July 2025)

Read an interview: “In Cynthia Blakeley’s memoir, investigating her family’s secrets to make sense of her own life,” The Boston Globe (Feb. 2025)

A hybrid memoir, The Innermost House interweaves stories from my precarious upbringing as a “townie” in a fishing village on Cape Cod with scholarly commentary on how we remember, why we forget, and the choices we make in our curation of the past. Through compelling personal and family stories, each of the book’s nine chapters addresses significant types of autobiographical memory, melding plot- and character-driven nonfiction with observations on narrative identity and the craft of memoir.

The book opens with the most unknowable memories of all, our “impossible” memories, inscribed not in consciousness but the body, or experienced but not always believed. From there it ventures into the power of intergenerational oral histories, the pull of family secrets, the disorientation—and reorientation—of recovered memory, and the intervention of dreams. Later chapters shed light on the dynamic between memory and narrative identity, the organizing and sometimes coercive power of scripts, the underappreciated mercy of forgetting, and the role of forgiveness in living more companionably with the past. Each of these larger themes is animated by personal stories of ghosts and hauntings, astonishing natural beauty and sly town politics, failures and crimes, chance turns and unconventional redemptions.

This is the story of a life and a family and not an academic treatise, but because thinking about how we remember and why we forget has helped me to understand and construct that story, I include supplementary notes at the end of the book. These notes offer support for my observations on memory, historical contextualization, literary references, and elaboration on important points. The endnotes thus comprise a vital companion to the text, a guide that makes explicit the process of crafting—or co-crafting, as is often the case in retelling the past—a memoir out of scraps of memory.

It is my hope that as readers live through the events and scenes I relate and catch glimpses of how they were brought back to life, they might consider ways to gather, perhaps even rediscover, their own fragments of personal and family memory, creating constellations and stories that add light and meaning to what the Provincetown poet Mary Oliver so rightly calls our “one wild and precious life.”